Breathing Spaces, or A Sense of Placed

My interest in landscape is not just restricted to history and archaeology. I’m just as interested in the modern urban landscape (of Liverpool in the case of this website), because it’s the product of everything that went before. Archaeologists recognise the ‘layers’ of landscape development as truly as they see the ordered layers in the side of a trench denoting Romans following Iron Age communities following etc etc etc. Sense of Placed delves into these layers.

And as I’ve researched Liverpool’s historic landscape and the landscapes of urban zones around the world (and as I’ve lived in several very distinct cities myself), I’ve come to realise the role landscape history plays in our day to day lives. This happens whether we think we’re interacting with ‘The Past’ or not.

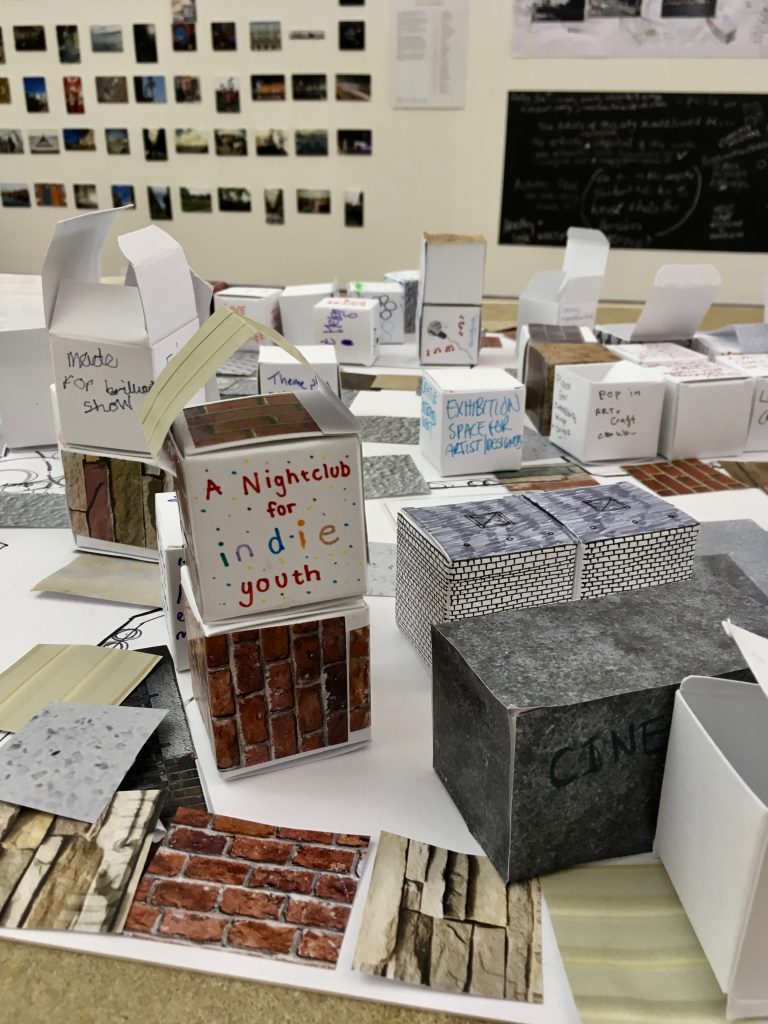

And so a project that naturally caught my eye started with a van called Ed, and has so far developed into Placed (‘Place Education’), which until Sunday 23rd September 2018 inhabited a slice of the old George Henry Lee building on Houghton Street.

Placed want to know what influences changes in shop occupancy, and the impact of those changes on the use of the surrounding area. In this way it ties in to my own interests.

Breathing Spaces

My encounter with Placed came in the form of a guided tour by Ronnie Hughes, who many readers will recognise as the author of the A Sense of Place blog (only available on the Wayback Machine archive: https://asenseofplace.com/). He’s also involved in local community initiatives such as Granby 4 Streets and the Mystery Literary Festival (though he’d be the first to tell you he’s just part of a team). And now a PhD in Sociology and History!

Having read Ronnie’s blog for what seems like the best part of a decade, I was very much looking forward to meeting the man in person, especially listening to him talk about a project where our respective interests overlap.

Breathing Spaces, giving the walk its title, are the spaces Ronnie has identified in any given city which let visitors to the centre can use to take a moment to reflect.

Ideal Breathing Spaces should be noticeably quiet – away from the bustle of shoppers, cars, buskers, soap-boxers – sheltered to lesser or greater extent from the elements, and Free. Free has a capital F for me because (taking a cue from the Open Source movement) it should be Free as in ‘Free Speech’ as well as in ‘free beer’. In its Free-ness it should be inviting, in that you should be in no doubt that you can come here, sit down, eat your own food perhaps, without being moved on. A truly communal public space that welcomes.

Do we have any of those in Liverpool? And how well do they match up to these ideals?

I must say now that these ‘ideals’ are ones I felt came across during the walk, and are not necessarily culled from a shopping list that Ronnie has made!

It was a small group on this, the third of three walks. This made it easy to exchange ideas and chat about our own takes on what Ronnie was describing. The youngest member of the group must have been no more than 10 years old, and even she was engaged with the things we were talking about!

Literally Going to Town

We first shared our ideas of what ‘going to town’ means to us. It means (to our group) shopping, socialising, going to work, doing touristy things and a few other things besides.

But this is in some contrast to the landscape of town, which can very easily feel like it’s all about shopping. This is particularly true since the arrival of Liverpool One. Town is a shopping landscape, and so Breathing Spaces might merely be seen as a ‘break from shopping’. But that would be to misunderstand what many people are in town to do.

Ronnie had promised to take us to the best Breathing Space first, before taking us on a tour of other spaces that don’t do such a great job. The walk set out from George Henry Lee’s and headed first to the garden of Bluecoat Chambers. Why is this garden such a good space? Well, it is a secluded space, quiet and green, with seats and benches. Although the gates are locked at the end of the day (and were locked when Ronnie did a reccie earlier that morning!) you can come and go as you like. Even better, some of the tables inside the Bluecoat are free for you to sit without being obliged to buy a coffee from the café there.

In many ways this is the ideal: a Free space where you can come whenever you like, and where you’re not obliged to carry on your purchasing. You can truly take a break.

However, where the Bluecoat falls down is its obscurity. On the other walks Ronnie has taken, many did not know of its existence. And of those who did, they (and this included me until today) assumed that all the seating inside is for customers only. But that’s not the case, so next time you need a moment to yourself, pop into the Bluecoat cafe, head to the tables next to the Children’s Corner, and take the weight off.

Placed in public squares, car parks and through routes

But Bluecoat was a model student compared to the rest of the class, who could learn a thing or two…

I’ll not bore you with a detailed itinerary, suffice to mention a few common themes which our encounters with the other open spaces looked at.

Free to Breathe

The places we visited were dotted across town. We stopped at ‘Mr Seel’s Garden’, just off Hanover Street. We visited a couple of ‘squares’ (often created through the demolition of old houses) in the Ropewalks area, and we inspected the Breathing Space potential of Liverpool One and Derby Square.

We talked about the responsibility for these areas, and the quality of the space there. Most of the spaces had seating in, but in every case this was lacking in quantity, faced away from each other (so you wouldn’t go there with more than, say, one friend in tow), and was definitely doing its best to discourage the homeless from staying too long. In fact, it seemed designed to prevent anyone from getting too comfortable.

The other common theme was wastage of space. The area outside the Court in Derby Square was huge and flat and broken only by electronic bollards and a few intimidating benches to one side. Part of Ropewalks Square off Bold Street was a privately owned rectangle of uneven flagstones. Formerly the site of Christian’s grocer’s, the place is now vacant, empty, and unused, and yet private. Besides the fact that its a shame the grocer’s was moved on by the owner, its a double crime that someone can ‘sit’ on this space and reserve the right to keep people from it. It should be part of a revamped Ropewalks Square plan.

And this square, in common with the other spaces we saw, felt more like a cut through, from one place to another. The paving pattern reflected this, directing walkers straight across. It isn’t a place to stop, to pass the time of day, to people watch. And yet it could be, with a little bit of clever planning.

There are mature trees in these spaces now, and a smattering of seating. With some decent landscaping, people could come to these spots to rest, chat, or spend a moment of quiet contemplation away from the rush. A path that wound around planting would help ‘trap’ people (in the best way possible) and encourage them to stay a while. Not to mention that such a space would be more attractive to everyone, passers-by included!

Responsibility

But with Freedom comes great responsibility. Who would care for these places? Isn’t maintenance and redesign expensive?

Well, is it any more expensive than the street sweeping that must follow a heavy Saturday night in the Ropewalks? Plus, as Ronnie pointed out, an increasing number of people are moving into these areas. You can imagine guerilla gardeners or ‘friends of’ groups attaching themselves to these pockets. You can’t imagine either of these things happening to them in their current ‘bronze throne’ incarnations.

Some of the ‘squares’ are surrounded by bars, who benefit from these public spaces to accommodate bigger crowds and generate that all important footfall. Although they do a sterling job of sweeping up the broken glass and cigarette butts on a (late) Sunday morning, perhaps they should be contributing to the beautification of what also happens to be a space used in the day time.

This clash of daytime economy vs nighttime economy was raised a few times. Couldn’t there be more integration and collaboration?

Optimism

By the end of the tour it would have been possible to feel that Liverpool had a rather sorry selection of lacklustre spaces. But on the contrary, Ronnie was optimistic. Firstly, these spaces are open. They’re not built on, and are not about to be (although who knows about the Christian’s site?). So that’s the first issue rendered moot.

Secondly, through initiatives like those that Ronnie and the Placed team are involved in, there’s a chance that such ideas can have an impact.

Placed is all about increasing the influence of the community on their local environment. It’s also about showing people just how much influence they can have. There is a lot of skepticism over how much say people have over the changing landscape. People either think they have no say, or are not listened to. While this latter issue is unfortunately often the case in practice (two-day ‘consultations’ on a completed Masterplan, for example), it needn’t be the rule.

Ronnie truly feels that this situation can be turned around, and is working actively, with many others, towards this goal.

Free Spaces

The potential to create indoor Breathing Spaces is already there in Liverpool too.

We talked about the Bluecoat cafe, which just needs to be publicised more. But there’s also plenty of vacant space all over the shop (if you’ll pardon the pun). George Henry Lee’s is one example, and there are countless empty shop floors – first storey and upward – down Church Street, Bold Street and Lord Street. We also visited Cavern Walks, which has a nice big empty shop which hasn’t had tenants in a couple of years.

Cavern Walks was built to house hundreds of Lloyd’s Bank staff, who were a captive audience for the shops on the bottom two floors. But Lloyd’s left, and Cavern Walks is not in a great position to get much passing trade. Hence the empty lots.

But if a Breathing Space was set up in there – a place where you knew you could bring your own food, sit a while, sit as long as you like – then it becomes a magnet for people at this end of town.

The same thing applies to other places where this might be implemented. The potential for indoor Breathing Spaces is totally untapped.

Organic Spaces

We talked about a few other factors. Masterplans like Liverpool One are dropped wholesale on an area, and we heard how it necessitates artificial measures like price controls in order to work. It’s a delicate balance, artificially maintained. This is in contrast to how cities built up in the first place, with businesses cropping up in response to need (with the odd Charter, ahem, to seed the first settlement).

We talked about how residential developments must include a minimum percentage of homes in the ‘affordable’ bracket. Ronnie suggests we should demand portion of indoor Free Space too, especially in town centres.

Towns they are a-changing

Modern town centres are highly planned machines for encouraging spending. But as people move back into the towns and cities they fled from in the 70s and 80s it’s going to become more important that we take into account the other aspects of life: relaxation, contemplation, wandering, thinking, and we’ll need to provide for these things too.

By Ronnie’s thinking, the ideal situation would be one where we have a chain of indoor and outdoor spaces across town where we can plan little breaks and retreats from city centre life. Places where we can predict a spot to sit and think. ‘Going to town’ would then become much more varied in meaning. In fact ‘doing nothing’ might be a meaning in itself! Towns would become just that little bit more relaxed, and attractive, to they eyes and to the feet.

Heritage Breathing Spaces

To bring it back to history for a moment (!), it did cross my mind that museums and galleries can play a big part in this, and to a great extent already do. Although their opening hours are set, there are few other places you have such great license to come in for free, sit where you like, and do absolutely nothing, should the feeling take you. These places also come with a great deal of ‘props’ to inspire a bit of thinking, and are generally peaceful without having the strict Quiet rules of libraries.

I wish Ronnie and Placed the best of luck, and will be following their progress. I also hope to see other groups doing similar things, and would like to see these ideas spread.

Meanwhile, I think I will be keeping my eyes open for previously unnoticed Breathing Spaces wherever I go. I’ll collect them in memory for future reference when needing a moment to myself.

Thanks again to Ronnie for the walk, and the sharing of ideas. I’d like him to know that the first thing I did afterwards was to take my home-made packed lunch to Bluecoat to sit inside and eat it at their tables with great relish!

More information on Placed

Placed home page: https://placed.org.uk/

Placed on Twitter: https://twitter.com/placeded

Ronnie on Twitter: https://twitter.com/asenseofplace1

Ronnie’s blog: https://asenseofplace.com/